“The Happy Prince” gains its moral force from the contrast between carnal friendship and spiritual friendship.

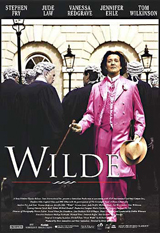

#OSCAR WILDE MOVIE. MOVIE#

By the end, the movie has begun to yell at us: Don’t you see, Wilde is the prince and Robbie Ross is the sparrow! The final title card is as subtle as a Goofus and Gallant strip: Ross spent the rest of his life honoring Wilde’s memory and promoting his work, and “is ashes are buried with Oscar. The happy prince is a statue who gives away all his gold and glittering gems to the poor, aided by the faithful sparrow who dies at his feet. The film’s title comes from one of Wilde’s fairy tales: a story he tells throughout the movie, first to his own children and then to the little brother of one of the boys he solicits for sex. Ross is a shade too desperate for Wilde’s favor, yet admirable in his faith. This film’s Ross is completely identified with his Catholicism to choose Ross is to choose the church, and vice versa. Still, the antagonism between Constance and Bosie is only a foil for the film’s real struggle, the battle between Robbie Ross (Edwin Thomas) and Bosie for Oscar’s soul. Alongside the silence of the wife and the cries of the baby, the mother’s innocence is a reproach. The mother cannot even imagine that men might sin sexually with other men her innocence is the scene’s twist, its stroke of comedy, but it isn’t ridiculous. The Italian mother does all the talking, while the wife cradles a baby. There is a startling Christmas Eve triptych in which Oscar’s sex party with a crowd of young men is contrasted not only with Constance and his sons’ cheerless celebration but also with the Italian women who come to harangue Wilde for debauching their son and husband.

There is humor in the contrast between Wilde’s devoted voiceover of a letter to Constance and his eyeing the rump of a cute waiter but the film honors the Wildes’ marital love. The scene in which Wilde struggles to decide whether he will write to Constance or Bosie-his wife or his lover-is filmed like any cliché addiction film’s tempted-by-relapse scene. The camera lingers on the crucifix, which isn’t even necessary the angle from which the priest is shot, emphasizing his humility before the altar, makes the same point more artfully.Ĭonstance Wilde (Emily Watson) haunts her husband. Oscar says he goes to a local church to view the attractive priest-but then we see this priest, an old man limping up to kneel and kiss the altar, as the voiceover muses on the primacy of love.

We know Wilde loves Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas (Colin Morgan) because Wilde puts up with endless humiliation from this blond parasite. Everett captures not only bravura but selflessness in Wilde’s degradation here, which is not surprising given that the film’s strongest message is that all love is self-abasement. He staggers atop a cabaret table and caterwauls “The Boy I Love” in heavy makeup.īut this cringing cabaret is a plot on Wilde’s part to defuse an incipient brawl.

“The Happy Prince” covers only the last few years of Wilde’s life, the battered years after his two-year sentence to hard labor for the crime of “gross indecency.” Everett emphasizes the sordid: His Wilde offers teenage boys cocaine and absinthe as partial payment for sex.

It is intensely interesting, especially when it touches on religion. This does not mean the film is uninteresting. Much of the film is heavy-handed melodrama without the irony and forgiveness that animated its protagonist’s moral worldview. The music tinkles with sentiment, the visual imagination is uninspired (Wilde has a dream, when his wife Constance dies, which would be more haunting if it were not illustrated by stock footage of a volcano), and the film switches back and forth between grotesquerie and tragedy rather than interlacing them. The film is intensely interesting, especially when it touches on religion.Įverett is not fully in control of this film. Oscar performs the role of the Man Who Met Christ in Prison, and it is only more amusing and piquant because he did really meet Christ in prison. His friend Reggie Turner (Colin Firth) quips, “Oh? What was she in for?”, but Oscar is having none of it: “Don’t joke, Reggie.” Everett, who is writer, director and star here, lets you hear all the curlicues in Oscar’s voice, the delectation of his own surrender. There is a moment toward the beginning of Rupert Everett’s new Oscar Wilde biopic, “The Happy Prince,” when Wilde interrupts his welcome-back-from-prison party to declaim, “I met Christ in prison.”

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)